‘Heavy lies the head that wears a crown”

King Henry IV, Part 2, William Shakespeare

Nothing can prepare you for taking on your first headship. I am sure the more experience you have, the better it will be. Perhaps going from Deputy to Head in the same school makes it a little easier. However, there are opposing opinions on that.

The hours, the personal commitment and steep learning curve which is required is nothing short of truly eye-opening and at times exhausting. For me, I absolutely loved being a Deputy Headteacher but the weight of responsibility and decision-making is, obviously, much greater when the buck stops with you as the Head. Although I witnessed my previous Headteacher go through this exact transition, experiencing it first-hand brings its own set of challenges.

As I come to the end of the first year, I consider a few key lessons which I have learned along the way. Obviously, these are my lessons and not generic to all those stepping up to Headship. They come as a by-product of my own leadership style, approach and previous experiences.

DERA (2003) identified that feelings of ‘professional isolation and loneliness’; and dealing with the ‘legacy, practice and style‘ of the previous headteacher were two of the biggest challenges facing a new Headteacher. Whilst that might be true, I found that the biggest difficulty was managing my own expectations of change. The five lessons below are a result of that direct challenge.

Lesson 1: Trust; then verify

This lesson comes from my previous headteacher who led a large outstanding school in southeast London. Essentially, when you are told something, or assured of something from any member of your team – trust them – even if you suspect that you have a reason not to do so. As headteacher, you then touch base to verify the information: you can do it by popping into class, picking up some books, speaking to children – the list is endless in a school. This approach allows your staff to feel valued, and not micromanaged, but also gives you the reassurances that you require to run the organisation.

As it turns out, there is a heap of research around operating in this way, and the recognition of when it works most effectively. Harvard Business Review (2013) identified that in creative industries (of which I consider teaching) that this practice is most effective. HBR also recognizes that trust can only work where clear boundaries exist. Staff members need to know the extent to which they can operate or extend said autonomy. For me, in a school where roles are clearly defined, this should pose no issue.

Keep it professional and let the evidence do the heavy lifting.

Lesson 2: Measure accurately

Research shows us the value of effective self-evaluation, with findings demonstrating that it can have a positive impact on school improvement, student learning, achievement, and school-community engagement (NSERE, 2022).

The same NSERE report highlights that for it to be successful, considerable trust and autonomy need to be placed in school leaders, and ‘top-down’ approaches driven by ‘high-stakes’ accountability need to be eschewed.

It will come as no surprise that I tried to accurately self-evaluate the school before I had even finished my first full term! I had been in my previous school for a decade. I knew the team, the data metrics, the systems—everything—inside out. So, when it came to supporting the Headteacher writing a self-evaluation, it was easy. However, when the setting is new, this is much more challenging to achieve. Taking the time to watch carefully is essential. And by watching, I really do mean it. Don’t allow yourself to make quick decisions when you can see that there is benefit to do so.

Take ample time to watch, understand, and prioritise—I can’t emphasize that enough. I found that the longer the school was in operation, the more I understood about its approach. If I’m being perfectly honest, it took most of my first year to be able to very clearly understand the vision and aims of the setting.

I also learned that the more change you undertake in year one, the harder that change will be to execute. When a change of headship happens, staff need clarity and stability, and change can be exceptionally hard to secure without full buy-in from those on the front line.

Slowly take stock of the organisation—it’s a marathon, not a sprint.

Lesson 3: Let go of previous experiences

I was exceptionally keen not to wax lyrical about my previous setting. I recall hearing about a leader who had arranged for their new school to spend time with staff from their previous one. For the new team, this was very challenging experience, leaving them feeling demotivated.

For me, I wanted to bring in all the experts I had worked with – not because the new team didn’t have the skillset, but because I wanted their thoughts and opinions. I already trusted them – they were known to me. One year on, I now see that this is unnecessary. By trusting the new team you are with and valuing and challenging their inputs / evaluations you can tap into the expertise that is around you in the new setting. I wanted to move quickly, have quick wins, develop robust systems, but doing this in isolation isn’t possible (or fun!). Trust the team around you and get their input.

I slowly learned to let go of the previous setting, but to carry with me the lessons I had learned whilst there. The systems I worked on wouldn’t fit my new setting but the skillset of implementing change is of course completely transferable.

Lesson 4: Saying no can be good! Get used to it.

Part of becoming a Headteacher is inevitably saying yes to different opportunities. I hate letting people down. But I quickly realised that I needed to do it to allow myself the capacity required to do the job well. The education support network attributes this as one of the issues they most commonly discuss through their services: capacity. They state on their website that saying no to one thing may allow you to say yes to something else. Are you taking on responsibilities that align with your own priorities – if you are, why? Simple advice that far too many of us choose to ignore until we are burnt out and it is too late.

However, saying no also extends to the staff team and children. You don’t do the organisation any favours by trying to please people. Get comfortable with saying ‘no’ in a kind and professional way. Get comfortable with delivering challenging messages and embrace that this – if you’re doing your job well – is all for the children which your school is serving.

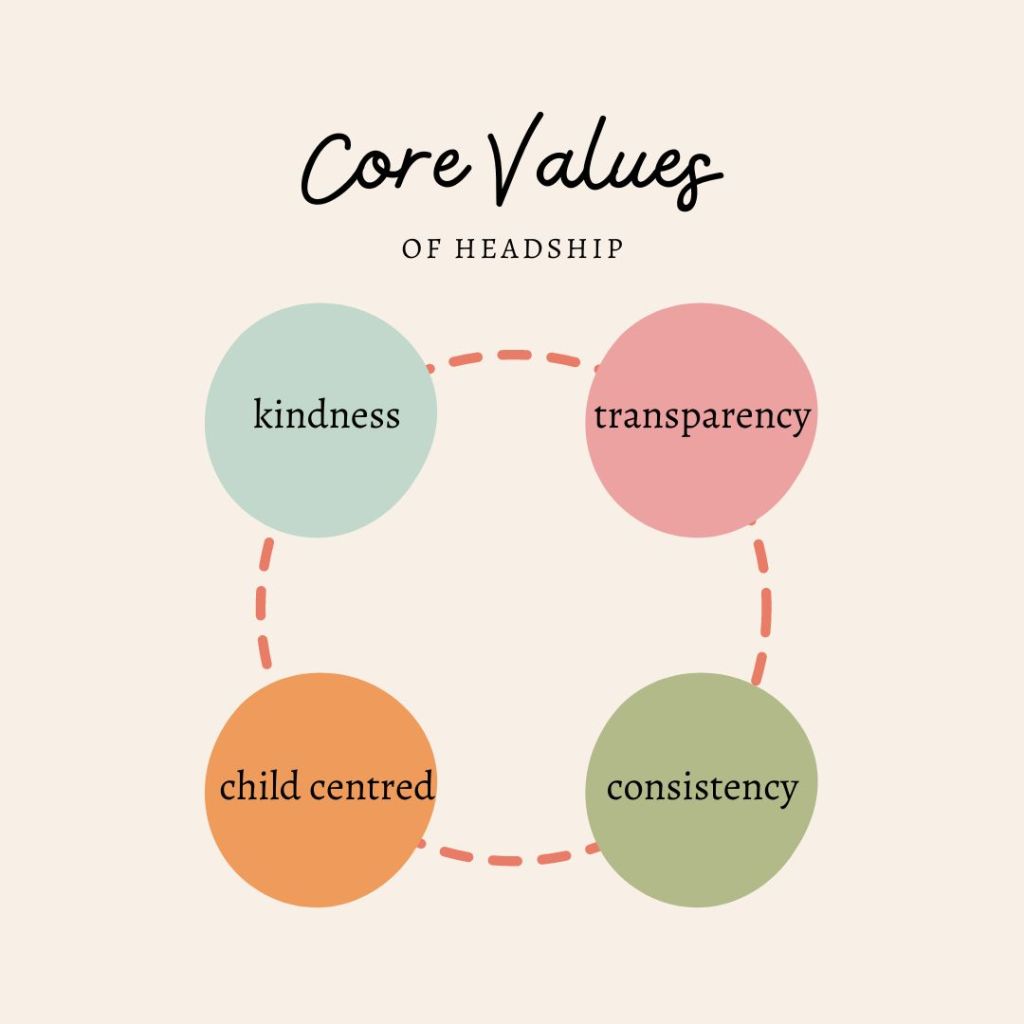

- Transparency:

- I seek to give my true opinion and thoughts, even when this might be uncomfortable or difficult – to support me in these situations, I let the evidence do the heavy lifting.

- I ensure that those who need to have information, have it, and that this information is factual without the addition of my own emotion or feelings on a situation.

- There are no hidden agendas and those who I work with can trust that my word is sincere and authentic.

- Kindness

- I want to lead from the heart with children firmly at the centre of all decision making.

- When faced with decisions, I seek to ask: what is best for the children; will this help the children at my setting succeed?

- I seek to develop policies which allow me to operate in a fair and empathetic way which are sympathetic to the difficulties of attending or working in a school setting.

- Consistency

- I want to be a leader who sticks to their word; not overpromising and under delivering. To do this, I seek to ensure that I consider my own ability and capacity when committing to undertake work or projects.

- I seek to attend all weekly meetings, being visible at key times and touching base with key team members, consistently.

- I seek to deliver consistent messaging, not diluting the message to suit the needs of others – aspiring to be consistently transparent.

- I seek to always prioritise my commitment as Headteacher of King’s Cross Academy when faced with competing agendas and asks of others.

By operating with the above set of ‘rules’ I have the opportunity to become an effective leader; by doing this, my senior team can know what to expect from me and will have confidence in making decisions in my absence – knowing what I would likely decide if I was present. This is the basis for developing a high performing staff team.

It’s worth noting that an MIT Management Review (2019) finds that leaders who can articulate their values have greater success in a range of industries, including education. However, the most successful of those are those who are flexible of thought. Values are not stationery and fixed but develop, adapt and perhaps even change as an individual’s leadership ability and experience grows. You don’t need to set a time to review them, but just allow them to naturally develop as time allows.

What would I do differently?

I’m not in the business of giving advice to others on their Headship journey, but if I was to redo my first year, I would go in with greater clarity on the aspects of education that are vitally important to me: both an a school leader and an teacher. I would use these in my early days to decide the areas in which I want to focus in on and to consider where I place energy in that first year.

If you don’t have clarity on this, you can expect the competing priorities of different departments and individuals to become challenging to manage.

Its the best job in the world!

To steal the title of Vic Goddard’s book… it is the best job in the world! Headship is truly varied and working with children keeps you on your toes.

We wish our time away quickly in schools, living for the next holiday or break. But, as I step into my second year of Headship, I am looking forward to being more present in the moment and enjoying the interactions and little wins that inevitably happen along the way.

Here’s to another year of reflections and learning!

Leave a comment